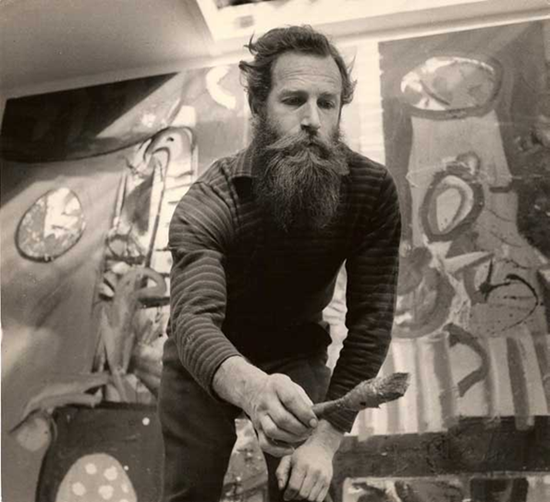

Fig 1: A young Alan Davie, photographed with dog (Belinda, apparently) – a man clearly in tune with the natural world

Fig 1: A young Alan Davie, photographed with dog (Belinda, apparently) – a man clearly in tune with the natural world

I first recall encountering Alan Davie’s (1920 – 2014) work at first hand, in the early 1990’s when visiting the Kelvingrove Art Gallery in Glasgow. A child at the time, I remember the effect these awesome paintings had on my young mind. The sheer scale, depth of feeling, use of rich colours and ethereal forms were like nothing I had experienced, prior to this important moment. Important because, I am quite certain now, that this event was when I first became fascinated with painting and more specifically abstraction within the medium. Davie’s death, just over a fortnight ago on the 5th of April, is the sad event which has prompted this unexpected deliberation, and my subsequent conclusion of his work, to be drawn. I find when thinking of Alan’s work, the fact I was a child when I first saw his paintings and that these objects were able to affect my observations in such a meaningful way, an interesting and correlated point. After reflecting on these events alongside the content of Davie’s work – both visually and thematically – I am inclined to think, the reason I was so drawn to this imagery as a child, was because my senses and judgements were far more innate and instinctive, and as a result the appeal of this artist’s creations and his visual approach held my attention in a way that I could neither explain nor feel the need or obligation to do so. This is not to say that all children are necessarily more inclined to find an appeal in abstraction; however I do suspect that in this instance that I was able to, unknowingly, accept what I was viewing as being both new and simultaneously totally familiar, in a manner that I could find an unexplained comfort in. My awareness of this intrigue, then as it is now, has an extensive appeal, which much like Davie’s work is precisely indefinable, yet considerations of, joyously attempted and therefore one feels inclined to do so again in the ensuing text.

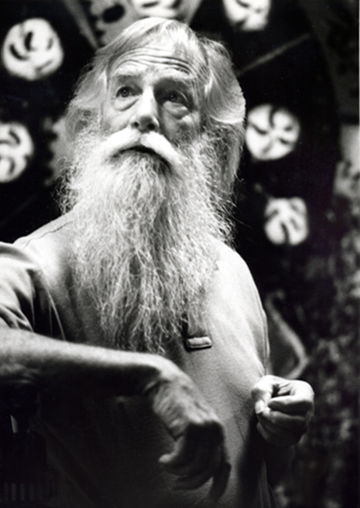

Fig 2: Davie the artist and shaman working in his studio, utilising his own ‘dip technique’, which is evident in much of his early work

Fig 2: Davie the artist and shaman working in his studio, utilising his own ‘dip technique’, which is evident in much of his early work

Fig 3: The Saint (1948) is an early painting of Davie’s, which has shades of Picasso coupled with the expressionistic, symbolic style of a Munch

Fig 3: The Saint (1948) is an early painting of Davie’s, which has shades of Picasso coupled with the expressionistic, symbolic style of a Munch

Born in 1920 in Grangemouth, Scotland, Alan attended Edinburgh College of Art from 1938 to 40. After which he conscripted in the army and served in the Artillery during the Second War. However, during this period he never experienced front line battle. Instead his time was spent in training at an aircraft base in rural Warwickshire, surrounded by fields, trees and rural nature; which is now said to have played a crucial part in his eventual creative focus and direction. His interest in poetry, both as a writer and student of were pursued at this time and much of the artistic principles gained from this creative pursuit subsequently led into his painting. An awareness of the poetry of Walt Whitman (1819 – 1892) & T.S. Eliot (1888 – 1965) subsequently blossomed. In connection with these concerns, a consciousness of nature and a human being’s fundamental connections with this ensued and became an ever-present aspect of Davie’s practice. The realisation of these factors was settled upon during these experiences and studies.

Fig 4: Jingling Space (1950) is a particular favourite of mine. A young artist, just getting by at the time, the painting is comparable to a fine improvisational jazz performance - an activity and discipline Davie was honing and adapting both as a musician and a painter, during this decade.

Fig 4: Jingling Space (1950) is a particular favourite of mine. A young artist, just getting by at the time, the painting is comparable to a fine improvisational jazz performance - an activity and discipline Davie was honing and adapting both as a musician and a painter, during this decade.

Davie’s approach to his work is primarily, deeply rooted in the improvisational nature of jazz music. A jazz musician of some standing himself, his concentration on the subconscious, embryonic state of the human mind and its capacity for extemporaneous creative development, is at the centre of his practice. During the 50’s Davie, like many other noted writers and artists utilising various disciplines, discovered and began adapting Eastern philosophies as part of their approach to their practices – the Beat writers being a noted example of this. The idea that art is a spiritual force that is in a sense, channelled through the physicality’s of the human body, was an ethos present in most of Davie’s paintings – particularly his earlier work of the 40’s, 50’s & 60’s – of which much of these ideas and principles had come from Eastern cultural and religious beliefs. The surrendering of oneself to a type of ‘native state’, where controlled impulses are allocated time and space in order to create different, unimagined forms of visual expression, was the central concern of Davie’s practice during this time. Davie appropriately described his approach to painting in this way:

a manifestation of spirit felt by a creative genius and passed to us through its conducting medium of form, as a wire can conduct electrical energy from one matter to another.[1]

Fig 5: Farmer's Wife No. 2 (Jazz Musician and Lady) (1957) is a highly erotic, spontaneous, pulsating and texture work; both physically – by adding grit to the paint – and visually through the sheer expressive freedom of its formation. A work that displays various hallmarks of the artist’s interest in eroticism and improvisational techniques.

Fig 5: Farmer's Wife No. 2 (Jazz Musician and Lady) (1957) is a highly erotic, spontaneous, pulsating and texture work; both physically – by adding grit to the paint – and visually through the sheer expressive freedom of its formation. A work that displays various hallmarks of the artist’s interest in eroticism and improvisational techniques.

Fig 6: Image of the Fish God (1956) is one of a series of 7 works of the same title. These images are informed by his interest in the primordial, shamanistic forms of ancient civilisations and beliefs.

Fig 6: Image of the Fish God (1956) is one of a series of 7 works of the same title. These images are informed by his interest in the primordial, shamanistic forms of ancient civilisations and beliefs.

At this time, this inevitably led to associations being made between his paintings and those of the new American Abstract Expressionists – and particularly the drip paintings of Jackson Pollack. This wholly simplistic comparison was one that Davie unsurprisingly rejected. Declaring himself, very much a “Scottish artist”; seeing himself in the Celtic and Pictish traditions and not in the Modernist cannon (although, this revisiting of ancient art and cultures of course, put his work very much within that particularly ‘Modern’ category). Whether consciously so or not, Davie’s art and the personality of the artist himself, became depicted as sort of shamanistic and a ‘man of nature’. A Super-8 film made by him and his wife Bili in 1960, of him working on various paintings in his London flat, stripped to the waist, with his legendary chest length beard, throwing dust and other debris onto the canvases, helped enforce this view of Davie ‘the artist’. The amalgamation of improvisational jazz, Zen Buddhist, Byzantine, Romanesque, pagan and early/pre-Christian cultures, became significant subjects and considerations within his work. His intrigue in exoticism and eroticism, which was evident in much of the visual imagery and other stimulated sensory accounts, found in the works Davie became immersive in, fused in his work with the spiritual intensity of his own deeply held Celtic traditions.

The manner in which this artist is able to depict the inner instinctive spontaneity of the human perceptual state through the use of abstracted, archaic forms and seemingly primordially subject matter, I find singularly individual and visually arresting. In fact, Davie is now often regarded as one of the first British artists’ post, Second War to have developed a form of abstraction within his painting. Not until latterly, and his work of the 70’s, 80’s, 90’s & 00’s, where figuration, symbolism, formalism and text within his paintings become more the predominate theme, does his work begin to alter some of its immediate attentions. These images contain far less of the overt dynamism and fervour, which Davie exudes in this earlier artistic phase(s). These paintings in my view, feel much more illustrative of the human sensory/spiritual development – even of the histories relating to some of these crucial historical episodes, in various respects – than they are of an actual occurrence of an emotive response to ‘being’. This work is still often captivating aesthetically and the colours exquisitely vibrant, however it’s far more visually descriptive qualities and controlled arrangements have a less evocative and lasting resonance for me, than previously was the case.

Fig 7: An example of the controlled pictorial symbolism that featured heavily in his later career. The Studio No. 28 (1975) is far more representational as an image than the paintings of previous decades.

Fig 7: An example of the controlled pictorial symbolism that featured heavily in his later career. The Studio No. 28 (1975) is far more representational as an image than the paintings of previous decades.

As Davie’s work is often allied to the Jungian position relating to psychoanalysis, as opposed to the Freudian notions of the unconscious and its emphasis on repressed drives (mainly sexual) originating from childhood and adolescent experiences, therefore his use of symbols, reducible objects and forms, have been considered in conjunction with a mutual, ‘collective’ thought process and a shared or comparable human psychological awareness. These signs do unquestionably become transferable or substituted for various meanings and explanations; however the artist himself is always wary not to allow any fixed definitions to take precedent understandably, due to his own overriding concerns with the singular, intrinsic creative act and the unearthing of a certain truth behind a human experience. These observations connect with the commonly received association, of the artist’s work with 20th century European Surrealism and his focus on “juxtaposing the sacred and the sacrilegious”[2]. Quite fittingly in this regard, is the inclusion of his paintings in Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1966 film Blow-Up – where a fashion photographer attempts to solve a possible murder by physically analysing one of his photographs, which he believes has captured a moment from this mysterious incident. The film’s subject matter, of scrutinising an object and a creative act in order to reveal a certain truth or mystery, coupled with Antonioni’s own improvisational treatment to his artistic discipline, seems analogous with Davie’s work and his treatment to the creative act.

When one now considers a comparable artist like Jackson Pollack for instance (a contemporary, a personal associate and a name which regularly crops up when reading texts about Davie), and the esteem in which he is held in by, firstly, in his native America alone and then by the wider art world as a whole, this contrast is startlingly dissimilar. As the critic and writer Robin Greenwood, when discussing Alan’s work of the 1950’s, recently described: “It is the culmination of a decade when Davie was without equal as a painter in the UK, possibly in the world.”[3] This is a judgement that I would concur with fully and would also add that his exceptional standard of paintings and productivity continued well into the next decade. Although in the ensuing decades the works became more ‘work like’ and somewhat formulaic (partly due to his own consummate standards), there was still continually the odd great picture, even in the last two decades of his life. Therefore, I find it incredibly frustrating that even within his native Scotland, an artist whom is regarded by many people inside the art community as being one of the most important painters the country has produced (and I would say the finest of the last century), has still not received the type of recognition and celebration that many of his contemporaries and also his predecessors have been granted – many of which I also believe to be far inferior to Davie. It is a sad reality if Scotland, and similarly the wider art world, do not begin to recognise the unbridled commitment and talents of this great painter. As a child, on seeing them for the first time on that day in Glasgow, I was completely transfixed by his paintings, a fascination that still shows no sign of abating. Therefore, that chance encounter of mine, on that day, I hope could be reciprocated for others. However, due to the still relativity stark widespread acknowledgment of his work, even within his own native country, such a meeting is sadly expected to pass many people by. As a result, I judge if there was ever a big summer retrospective to be had at the Scottish National Gallery, it would be Alan Davie, and at this time, particularly appropriate and poignant I feel, in the year following his death.

![The Alchemist's Mirror No. 1 [Opus 1357]](http://www.nationalgalleries.org/media/38/collection/GMA%204325.jpg) Fig 9: Painted in 1997, The Alchemist's Mirror No. 1 [Opus 1357], is a fine painting from Alan’s later career. The richness and texture of the paint is coupled with an intriguing composition; his interest in African art is also clear to see here.

Fig 9: Painted in 1997, The Alchemist's Mirror No. 1 [Opus 1357], is a fine painting from Alan’s later career. The richness and texture of the paint is coupled with an intriguing composition; his interest in African art is also clear to see here.

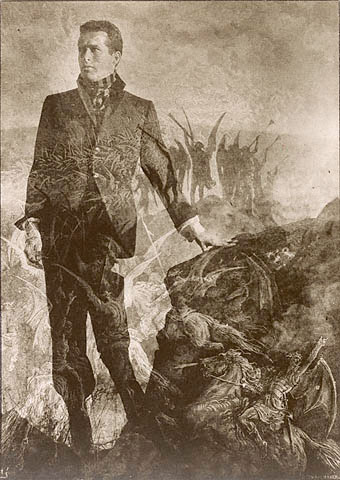

Fig 10: Alan in later life, an artist to the core and in every sense – the trademark beard was a constant throughout.

Fig 10: Alan in later life, an artist to the core and in every sense – the trademark beard was a constant throughout.

[1] Alan Davie, In the Quest of a Philosophy of Beauty: A Journal (1948), p. unpaginated.

[2] Robert Melville, Contemporary British Painters: Alan Davie(Gimpel Fils: London, 1961), p. 1.

[3] Robin Greenwood, Alan Davie and Albert Irvin at Gimpel Fils, (forabstract critical, 14th May 2013)

1) Andy Warhol, Untitled, 1987. 2) Francisco Goya, Tampoco: Desastres de la Guerra 3) When Shall We Meet Again? (1-3 Courtesy of Richard Harris Collection)

1) Andy Warhol, Untitled, 1987. 2) Francisco Goya, Tampoco: Desastres de la Guerra 3) When Shall We Meet Again? (1-3 Courtesy of Richard Harris Collection)